Unlicensed drivers kill a lot of people.

Driving is an inherently dangerous activity. Drivers kill about 100 people a day in the USA and have done so consistently for more than 60 years. Unlicensed drivers cause fully 1 in 5 of these deaths.

That’s appalling. What can we do to fix this?

Looked at naïvely there are three things we can do with killer drivers:

- Pretend roadway deaths as “just accidents” and let killer drivers off lightly.

- Treat killer drivers harshly and give them long prison sentences.

- Do our best to prevent drivers from killing people in the first place.

Contemporary society mostly chooses Option 1. Since driving is a very useful activity, we accept needless deaths as simply a cost of doing business. We are too empathetic to drivers and not empathetic enough to their victims. But this is a horrible, unfair way to run a society and it is inherently unsustainable.

What about Option 2? Senseless taking of innocent lives inflames people’s sense of outrage. It feels good to harshly punish killers, even if the killing was “unintentional”. But steep penalties won’t bring victims of traffic violence back, nor does it necessarily improve street safety.

Option 3 might be our best bet. So let’s look at one easy and inexpensive way to help keep dangerous drivers off the road.

Have the cars themselves enforce the licensing requirement

To drive a car you need two things: permission from the owner to use the car, (the car keys), and permission from the government to use the roads (in the form of a license). If you lose your car keys, the car itself prevents you from driving. Wouldn’t it be great of absence of a valid license also prevented a car from operating?

Smart chips – technology from the 1990s – can help

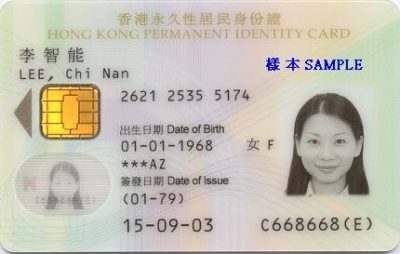

Suppose we equipped licenses with smart chips (the gold square thing in the figure below). Smart chip equipped licenses (for convenience I will refer to this as a “smart licenses”) can conveniently and inexpensively improve street safety by preventing people lacking a valid license from driving.

In the corporate world it’s increasingly common for people to log onto their computer by placing a smart-chip equipped ID into a card reader and typing in a personal identification number (PIN). This is similar to the way people use an ATM. This “two-factor identification” provides strong authentication; it’s far more difficult to “crack” than a password, and it’s much harder for a user to share their logon credentials with another person (since two people cannot be using the ID at the same time).

In a society that requires “smart licenses”, starting a car would require these three steps: car keys would be required just like we do today, plus the driver would place their smart-chip license into a card reader and enter their PIN through a keypad or touch screen. The use and function of car keys would be the same as they are today – they would still represent permission from the owner to use the car. The other two steps confirm the driver has the government’s permission (i.e., a valid driver’s license) to use public roads.

Three ways this would improve roadway safety

Smart licenses would improve roadway safety in these fundamental ways:

- Prevention: The most obvious way smart licenses will make streets safer is it will prevent people who do not have a valid license from driving. One need not look too hard to see lives lost to unlicensed motorists.

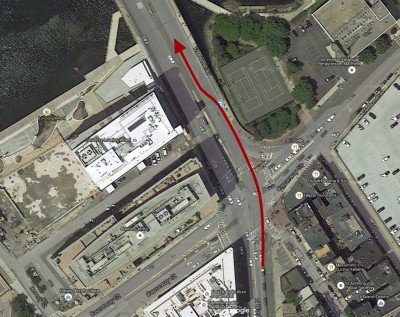

- Accountability: A less obvious benefit is that smart licenses will help bring hit & run drivers to justice. Recently a man was killed by a hit and run driver. The police found a car that is likely the one used in the killing. But investigating the car for forensic evidence is no guarantee the police will be able to identify the driver. Furthermore it’s likely there won’t be enough certainty about who was driving for a jury to convict. In a smart license society, driver information is saved to the vehicle data recorder, making it easy for police to identify the operator and making it difficult for a driver to deny culpability.

- Responsibility: Smart card licensing can improve road safety in many additional small but meaningful ways. They can provide fine grained restrictions on vehicle use based on the driver’s license type:

- Enforce restrictions for new “provisional” drivers. In many places, teenage drivers (a proxy for “inexperienced” drivers) have restrictions regarding everything from cell phone use to lawful hours of operation. Some of these restrictions (e.g., hours of operation) could be enforced by the smart license.

- Furthermore, a smart license could provide a better measure than driver age to determine experience. A small amount of on-chip memory can keep a log of how many hours experience a driver has, and automatically open up new capabilities as milestones are reached (e.g., allow late night driving after 100 hours of driving experience, etc.).

- Some vision-impaired drivers have a night restriction. Smart licenses can enforce this restriction.

- Prevent people who lack a Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) from driving trucks.

Smart licenses are inexpensive!

Putting a smart chip on a license would add less than a dollar to their cost, and card readers currently cost about $15. Economies of scale would bring these prices down dramatically when implemented in every car and every license.

Timeline

Like most every other safety system mandate – seat belts, air bags, tire pressure monitoring – smart card licenses and enforcement would phase in over time. The average age of cars on American roads is just over 11 years, so even if we implemented smart licenses today it would take a long time before the majority of cars were card-reader equipped.

Which is all the more reason to start right away.

Letting people literally drive away from a crash that kills, or locking people up for unintentionally killing someone are both poor solutions to vehicular violence. The only solution that benefits everybody is to make streets safer – something we can get much closer to if cars themselves were a means to enforce the requirement that all drivers have a license.