[Edited: 24 January 2016: Added suncalc.net and accidentsketch.com links and descriptions as tools for describing your event]

Cyclists: when a professional driver hazards you on the road, you can strike back. You should strike back. Strike back by reporting them to their employer and demanding the employer take action. Foremost, you might get justice for the acts of malice or negligence that put you in harms way. And importantly, you will help get bad drivers off the road that might bring harm to you or other vulnerable road users in the future:

This essay will share my recent experiences, outline some elements of how to tell your story effectively, and introduce some tools.

My recent experiences: I’m a very good at city cycling. I know how to interact safely with traffic, which includes allowing space to mitigate the risks of driver negligence. As a result, I’ve been able to go for months – or even years – without any scary interaction with motorists. But recently over a four-week period this fall, I’ve had three very close calls while riding. All three events involved professional drivers choosing to pass me unsafely. All three also resulted in me filing formal complaints with the employers of the drivers. The stories are linked below:

- 21 September 2015: Bus driver chooses to execute unsafe pass on College Avenue in Somerville, MA.

- 30 September 2015: Bus driver chose to pass me unsafely on North Washington Street, Boston.

- 8 October 2015: Commercial vehicle driver chooses to execute unsafe pass on North Washington Street, Boston. Twice.

I’ve received acknowledgments from the MBTA that appropriate action will be taken to improve the safety of their drivers. I have little faith in this, but perhaps if these same drivers receive written complaints in the future, they will be disciplined. I got an excellent response from the employers of the commercial driver. They are taking action to have him removed, but due to contractual protections this outcome is not certain. My personal view is that if your job is to drive, you better be good at it – all the time. I have no empathy whatsoever for a bus or commercial truck driver fired from their job for endangering fellow road users through malice or negligence.

Telling your story

Hopefully it will be a very long time before another driver threatens me with their vehicle. And I sincerely hope bad driving won’t endanger my friends – or anybody for that matter. But the reality is, we still live in a culture where “road rage” is an accepted part of daily life and where drivers boast that they “drive like a masshole”. So, in case you or I ever need it in the future – here are some tips on telling your story:

- During and immediately after the event: Get as much information about the participating parties as possible. Parties include the offending driver, their vehicle, and any witness information.

- Get pictures of the vehicle, especially license plate or any identifying numbers permanently affixed to the vehicle.

- For buses: MBTA buses have a unique four-digit number painted on the vehicle. This is often more visible than the license plate and it is far more important than the bus route number.

- Get a picture of the driver if possible, but keep in mind that this can be considered a threatening gesture.

- MBTA bus drivers all have a driver ID number – think of it like a police officer’s badge number or an employee ID. If you can, ask the bus driver for their ID.

- Get information recorded as soon as possible! I’ve tried the trick of repeating a number in my head in a loop trying to hold the memory. This ultimately does not work for me. A better approach is to pull over immediately and write info down. In my case I’ve written a text message to myself to store license plate numbers or other info.

- Behave yourself! If your story leads to legal, civil or administrative action against the driver, the last thing you want is for the story to include you slinging obscenities and throwing punches.

- Get pictures of the vehicle, especially license plate or any identifying numbers permanently affixed to the vehicle.

- Write the complete story as soon as you safely can: Try to start writing soon after you get home and try to complete and submit it to authorities within about 24 hours of the incident.

- The longer you wait, the less authorities will take you seriously.

- The longer you wait, the more your memory of events will drift.

- Your motivation to pursue the matter drops dramatically after a day or two past the event. Your blood might be boiling over a near death experience today, but three days from now you’ll have moved on.

- Write a clear, honest and compelling story:

- Clarity:

- Open with an overview and what you would like to see done about it. “One of your drivers put me in peril through their reckless or intentionally dangerous driving. In the interest of public safety, you need to stop letting that person drive your vehicles…” is a good start.

- Use pictures. Embed them right into the flow of the narrative. Label the pictures with a figure number and a brief description of the picture, e.g., “this is the truck just after it ran me off the road.” Even if you did not have a camera, you can include pictures – see the next three items below.

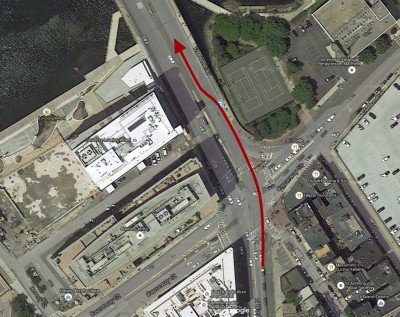

- Consider including a map. Google Maps is a great resource. Zoom in on an overview of the event location and get a screen capture of the area. If you’re good with computers, you can draw arrows and numbers to key locations with graphics software. But don’t be afraid to go ‘old school’ – you can print and annotate the map with ink.

- Give the reader perspective.

- Google Street View, part of Google Maps, can show roads and intersections from a street level point of view. Take screen captures of key locations so that you’re sure the reader understands the environment in which you were threatened.

- Consider creating a cross section view of the roadway, if that lends clarity to your case. Use http://streetmix.net. Streetmix is a tool for designing a street level view of roadways. It can fill the same function as a Google street view picture, if for some reason the street view is inadequate.

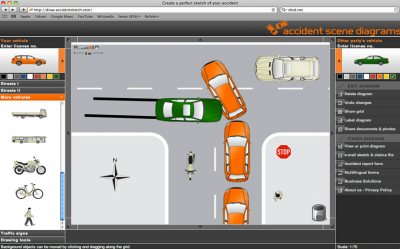

- Draw an overhead view of your crash using accidentsketch.com.

- Walk the reader through a timeline. Give a timeline of the events, and try to keep it flowing. If there’s something in the middle of the chronology that needs in-depth description, it might be better to talk about it briefly and promise to go into detail later.

- Make the story timeless. Legal, civil and administrative procedures can take time to fully unfold. Months or even years after an event, will you remember the weather, the position of the sun, or other relevant contextual factors? Consider using tools to capture these contextual elements:

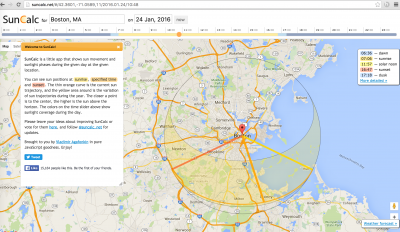

- Talk about the sun. Address up front whether sun glare might have been a factor in your own visibility of the visibility of other parties. You can use www.suncalc.net to show the position of the sun for any date, time and location:

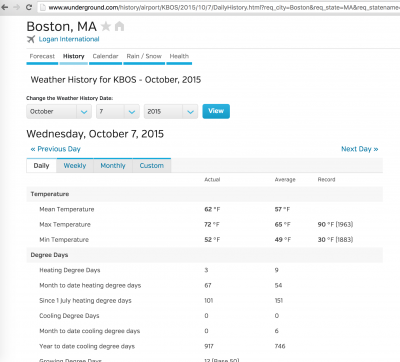

- Describe the weather. How was visibility? Was it a clear day, or was there rain, snow or fog to reduce visibility? You can use www.wunderground.com/history to capture weather for any given date, time and location.

- Talk about the sun. Address up front whether sun glare might have been a factor in your own visibility of the visibility of other parties. You can use www.suncalc.net to show the position of the sun for any date, time and location:

- Honesty: I’m not insinuating any of us will lie or embellish our narratives. But it’s easy to drift toward conjecture. Endeavor to stick strictly to facts.

- The facts will necessarily include dull minutia about the context. Where were you, what was the time and date, which direction were you going, how was the visibility. Include every relevant fact you can recall, but feel free to emphasize the facts more relevant to your story. For example, you might have already said that the event happened at 7pm on a rainy evening in October, but feel free to also spell right out for the reader that it was dark and road conditions were slick.

- Your emotions are also facts. It is perfectly acceptable – and highly effective – to tell how you felt within the narrative: “The driver was bearing down on me honking the horn constantly. I had nowhere safe to go, and I was terrified!”

- The driver’s motives and emotions are assumptions, not facts. Avoid them if possible. But at key points it’s OK to suggest possibilities: “At that point, either the driver did not see me or he intentionally drove straight at me. And given the visibility, the amount of time I was in front of him, and other factors – either possibility indicates he is not qualified to safely drive”.

- Make the story compelling. I don’t mean you should go out of your way to fill the story with adjectives. And in fact, if you follow all the tips I’ve written so far, your story will totally be compelling enough.

- Try to avoid big bunches of pictures or long stretches of prose. Instead, try to weave the words and graphics together in a balanced way. Notably, even if you did not take any pictures during the event, you can at least have an overhead view of the location and street level views from Google Street View. And if you don’t have a picture of the exact delivery truck that cut you off, maybe you can find one on the Internet and caption it appropriately: “Not the truck that swerved into me, but very close in type and size”.

- Try also to break up long stretches of factual narrative with emotion or some personal facts that help you to be seen by the reader as a person: “It was a beautiful day, I was looking forward to getting home to make supper for myself and family…”

- Clarity:

- Proofread:

- If possible, take a break once you’ve written the story and come back later to proofread. Ideally you should sleep on it, but if you don’t have that much time (recall I suggested you submit your story within about 24 hours of the event), try to at least go for a walk or eat a meal between writing and reviewing.

- Read your story out loud – even if you’re all alone. I find that reading my stories aloud helps me catch more errors and factual omissions.

- Ask a friend to proofread. This is the best approach. If you’ve left out crucial facts in the timeline, or if you’ve failed to explain why some element of the story is important, an impartial third party will ask for clarification.

- Submit your story: This can be the most difficult part of the process, but it’s also the most important. Find out where to send your story, then submit it with a clear, assertive request for follow-up.

- Talk to a person: If possible, use resources like the company’s web site to get a number to call. Try to get in touch with somebody in management, the legal department, or someone who works with company safety. Try to get to talk to that person – not an administrative assistant.

- If you connect, them you have a written narrative of an incident and you’d like them to read and get back to you.

- If in spite of all efforts you can’t talk personally to someone in a position of authority, ask (presuming you’re at least talking to a person not a machine) that person how to get in touch with leadership via email.

- Follow up with email: Use the body of your email as a ‘cover letter’ and send the narrative of the event as an attachment. In the email body:

- Reference your call. “As discussed earlier today…”

- Ask for concrete action. “Your employee demonstrated he does not know the rules of the road. At the very least, he needs to be trained…”

- Make certain they know how to get in touch with you. Since you sent email, they’ll have your address. But feel free to add other contact information and tell them the best time to reach you.

- Make sure to tell them you would like a response. “Please contact me within the next few days and tell me how you will be handling this matter” might be appropriate.

- Talk to a person: If possible, use resources like the company’s web site to get a number to call. Try to get in touch with somebody in management, the legal department, or someone who works with company safety. Try to get to talk to that person – not an administrative assistant.

- Share your story: Don’t hesitate to share your story with others, especially others in positions of authority, if you think it’s appropriate.

- Advocacy organizations: Reach out to Livable Streets Alliance, Boston Cyclists Union, or the Bicycle Committee of whatever city the event occurred in.

- State level legislators: If you think your story has broader implications on state motor vehicle laws, contact your state senator and representative. For example, maybe your story speaks at a broader need to reduce speed limits in Massachusetts cities.

- Find out who your senator and representative is here: https://malegislature.gov.

- Chairpersons of the Joint Committee on Transportation are

Thomas M. McGee (Senate Chair, Thomas.McGee@masenate.gov) and William M. Straus (House Chair, William.Straus@mahouse.gov)

- City government: Contact the mayor’s office, and depending on the specifics of the event, file a report with the police.

- The Press: I have no experience here, but if your story is particularly noteworthy, try to get it published.

In summary, it’s important to tell our stories. It’s our one way to fight back against reckless driving and automotive bullying. Hopefully the essay above will help us all be better story tellers leading to better outcomes.